This piece grew out of an assignment for my PGCE, which involved writing a short story and reading it to a class of students. As my Year 7 class happened to be studying Greek myths, I thought it would be convenient to base my story on one of those myths, using the audio tales recorded by Daniel Morden and Hugh Lupton for Cambridge University as a model. I chose the myth of Lycaon because Morden and Lupton’s version is rather short, and so left me with plenty of scope for embellishment. The horrific elements would be bound to appeal to a significant proportion of my students, yet they might also be a little too horrific for some. In order to offset this, I decided to leaven the horror with some broad comedy involving pizzas with pineapple and sweet potato toppings. This may have been a mistake, for while the students enjoyed the story, some of them found the tonal mixture too jarring; they tended to prefer either the horror or the comedy. In the revision that appears below, I have removed the broadest comic elements (no more pizza), while retaining a few slightly less broad gags.

In the city of Arcadia, such things as kindness and good deeds were unknown—only greed, dishonesty and hatred. The people lied and stole and murdered without shame. Strangers would be robbed and buried alive. Neighbouring cities would be surprised at night, looted and set on fire. The old and the sick knew no support or protection there, only mockery and ill-treatment. Every outrage the citizens committed would be accompanied by howls of laughter, as if to kill, to maim, to steal were great jokes. Among this rabble of villains, no-one was fouler or more villainous than the king, wolf-hearted Lycaon, and his fifty detestable sons, whose cruelty knew no bounds. Cries of pain and anguish, coming from the palace, echoed ceaselessly through the bone-littered streets. The walls of the royal treasuries bulged and cracked with stolen gold; the granaries overflowed with stolen grain. The air hung heavy with the acrid stench of blood, which in Arcadia was judged the sweetest smell of all.

Reports were not slow in travelling. They travelled far, as far even as Olympos, abode of the gods, whose ruler, mighty Zeus, the cloud-compeller, received the news with a stern frown. Such acts, he thought, were not unknown among mortals—they were not unknown among gods—but could he permit them to continue so openly, so impiously?

“These Arcadian dogs insult me!” he complained to his queen, ox-eyed Hera, who listened with a serene smile. “Have they no heed of my divine wrath? Have they forgotten their dues towards me?”

And great Zeus shuddered in disgust, and as he shuddered, there were earthquakes and landslides below, and many people died.

“Great king,” said Hera, “they cannot pay their dues if you bury them all under rocks”.

“Not all, dearest queen,” Zeus replied gloomily. “Not all”.

“Be sparing in your divine wrath, my love. Do not act in haste. Go to Arcadia yourself. See with your own eyes their crimes, that you may better judge them. If you punish these Arcadians, let their punishment be fitting. Let it be known that the work is yours.”

“What punishment can hope to fit such wickedness?”

“Mighty Zeus,” said his queen, “there is no mind that can match yours for perfect wisdom.”

The terror-bringing mouth of the king of the gods opened to speak, and stayed open, and then shut, without issuing a sound. And then it opened again, but still there was no sound, and then it shut once more. The stern brows of all-knowing Zeus knitted into a frown.

Ox-eyed Hera sighed, and smiled another serene smile, and then she gently bent her beauteous head closer to her husband’s ear. And as he listened, the mouth of the king of the gods was soon smiling too.

The next evening, a stranger, hobbling along the streets of bone-paved Arcadia, came to the immense gates of the royal palace and requested entrance. He was an old man, dressed in torn and dirty rags, whose dirty, bedraggled beard reached almost to his feet. His skin was a sickly shade of pale green spattered with blotches of purple; his few teeth quivered as he spoke; his eyes were milky and distant. The breath that came from his mouth was rank. Only the sternness of his brow gave any hint that this filthy, feeble old man was not quite what he seemed.

The guards laughed at the old man’s request, for how could such a wretched creature imagine that he could be admitted to the palace of the great king Lycaon and his fifty noble sons? But still, they told the king, and Lycaon and his sons came to the windows and balconies of the palace to gawp, and they laughed, too. But rather than send him away with a kick, as they would normally do, Lycaon decided to grant the extraordinary request. “My boys,” said the king as he howled with laughter, “we can amuse ourselves with this one.”

And so the stranger was ushered into the dining hall of the palace, and given an honoured place at the table.

“Old man,” said Lycaon with a grin, “tonight you shall be served a dish such as you have never been served before!”

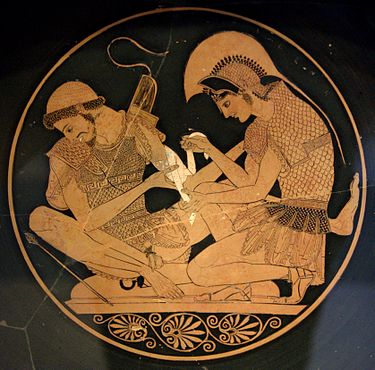

And with that, he took his fifty sons into the kitchen, all of them laughing and laughing, though only Lycaon seemed to know what he was laughing about, for amidst the laughter, his sons exchanged a few uneasy glances. When they got to the kitchen out of sight of the old man, Lycaon pounced on long-locked Nyctimus, the youngest of his sons, and bashed his face on the stone floor. Then he drew his sword, and before Nyctimus could get up, he cut his throat with as little feeling as a shepherd kills a dog turned blind and useless with age. The bright blood poured onto the floor like young, well-mixed wine, and it pooled around the feet of the forty-nine princes, who watched as their father cut up and butchered their brother. And Lycaon was laughing as he went about his work, laughing crazily, and his forty-nine sons watched him laugh, and soon they were laughing too, and, in his last dying breaths, even Nyctimus laughed, for in his last moments of life as the last drops of blood drained from his shivering body, he understood the joke.

The stranger, seated at his honoured place at the table, had begun to wonder if he would ever get his food. His stomach rumbled angrily. What could be the cause of all this delay? Certainly, the dish Lycaon had in store for him must be wonderful indeed if it required so much time to prepare. Just as the stranger was on the point of sending a servant to ask how much longer he would have to wait, in came Lycaon, followed by his forty-nine sons. The stranger counted them. Had there not been fifty when they were here before?

“Old man,” said Lycaon, “I promised you a dish such as you have never been served before, and that is what you shall have.”

He clapped his hands, and a servant entered, bearing an enormous, dazzling golden bowl. The servant bowed slightly before the stranger and set the bowl in front of him. The stranger peered at its steaming contents and sniffed its aroma. A stew of some kind. He stirred it slowly with a silver spoon.

“I thank you,” he said, “great king of Arcadia, for the honour of this meal. What is it, if I may ask?”

“You may ask,” said the king graciously, “and I will answer. We Arcadians eat this before toil and before battle. No feast is without it. It will give you warmth, health and strength. The power of a God will course through your hands”.

As Lycaon spoke this last word, a slender hand, severed roughly at the wrist, surfaced in the stew while the stranger stirred and stirred. Lycaon could restrain himself no longer. He clutched his stomach and staggered on his feet as he broke into howling, uncontrollable laughter, tears rolling down his cheeks. And his forty-nine sons started laughing, and they could not control their laughter, and they howled and howled and rolled about on the floor. And a sudden gust of wind blew in through the window, and blew over the top of the enormous golden bowl, and it seemed as if a faint howl of laughter issued from the bowl as the wind passed over it. The great dining hall of the royal palace of Arcadia echoed in howling laughter.

The stranger, too, laughed—but not for long. His laughter froze. His eyes flashed. His stern brow became even sterner with fury.

“Howl on, you animals,” he said quietly. “Howl on, and never cease your howling.”

And Lycaon and his sons kept howling with laughter, howling and howling, until their howls became louder and longer, and seemed less like laughter, until they were not laughing at all, only howling. And they did not stop howling as they saw, with horror, their mouths and noses grow and grow into long, hairy, whiskered snouts. They did not stop howling as claws sprouted from their hands and feet, as their ears spurted outwards and upwards, as tails shot out at the base of their backs. Lycaon and his forty-nine sons did not stop howling as they felt themselves forced onto all fours, as their torn clothes dropped to the floor, as sharp teeth drove their way painfully through their aching gums. They did not stop howling as they beheld the wretched old stranger throw off his rags and reveal himself as mighty Zeus, the cloud-compeller, two blinding beams of light blazing from beneath his stern brow.

“Gaze on me, you wolves,” he bellowed, “and know that your punishment comes from the king of the gods!”

With that, he vanished, and overhead there was a deafening peal of thunder, and lightning struck the palace, and the wind and the rain battered and lashed the people of Arcadia, who became frightened, terrified, and called upon sky-ruling Zeus to forgive them, swearing that never again would they descend to the evils that had been their custom for so long, that they would change their ways, that they would show kindness and consideration and seek always to help those in need, and try very hard not to murder them. Slowly, the clouds dispersed; the rain eased; the wind died down; the thunder and lightning ceased. The people of Arcadia rubbed their eyes and beheld the ruins of the palace, and amidst the smoking ruins, a pack of wolves, fifty of them, blind and howling. The people of Arcadia chased the wolves deep into the forests, where they have since remained—howling, forever howling.