A voice cried for pity

the tearful bird,

entombed in stone,

weeping ever in endless sorrow

always and always

new shapes of woe,

like a savage creature

much wronged. . . .

[A poem I wrote way back in 2010, now republished to mark Ratzinger’s death]

A lovely day, Holiness, don’t you think?

Here’s a nice cool cocktail for you to drink.

Have a chocolate tart, or a juicy pear.

Shall I fluff your cushion, adjust your chair?

I’ve got this soothing oil here; let me anoint –

Stop crawling, boy. Get to the fucking point.

Holiness, Signor Berlusconi sends greeting.

Ach! I hope he doesn’t want a meeting.

I cannot stand that tanned and toupee’d twat.

Remind me to arrange a concordat

With Iran; a fatwa should do the trick –

Get some wild-eyed nutjob to waste the prick.

His continued life, I cannot endure.

Such thoughts, your Holiness, are most impure.

You expect my mind to be without taint?

I’m the goddamn Pope, dumbass, not a saint!

Well, what does little Silvio want now?

I doubt it’s something the Church should allow.

A petition, your Grace, to effect a change –

Some doctrinal details to rearrange.

The Prime Minister admits to his vice,

But carnal misdeeds are so very nice.

He’s not an easy man to satiate;

His horde of harlots numbers eighty-eight,

Yet even these can’t satisfy his lusts

Or meet his burning appetite for busts.

But, reflecting on his mortality,

He’s been stirred by a strange morality.

Terror of hell now makes him palpitate;

He’s anxious to avoid a dismal fate.

For his ease of conscience to be ensured,

His adulterous past must be abjured.

Signor wishes to lead a blameless life,

Yet cannot rest content with just one wife.

Might he be permitted a couple more?

Monogamy, he claims, is such a bore.

Polygamy’s the answer, so he says,

But receives at present papal dispraise;

To amend this dogma is his request,

So that his many amours might be blessed.

Declare each Catholic female his spouse,

And all his conquests will be kept in-house.

Does he take me for a total duffer?

Of all the bullshit I’ve had to suffer,

This is the biggest pile of stinking crap

That’s been excreted on my ageing lap.

Why should I make this outrageous decree?

Signor offers a most substantial fee.

That puts the matter in a different light.

I’m not convinced it’s altogether right,

But sometimes intransigence must give way

When affluent fools are prepared to pay.

Your Grace is quite astonishingly wise.

But you’re looking tired; I’ll massage your thighs.

My previous posts about Dom Casmurro by Machado de Assis have avoided reference to the major plot developments that occur in the latter part of the novel; from here on in, however, I will be discussing the whole book freely, so if you haven’t read it, you may want to give this and following posts a miss. Even if, like me, you’re not normally bothered by the idea of spoilers, you might want to think twice before reading ahead here, as I found the cunning with which Machado springs his nasty surprises on the reader a fundamental part of what he’s up to (although I do wonder how the book is received by Brazilian readers; how much of the story do they know before casting their eyes on the first page?). In this post and those that follow, I will mostly refer to the protagonist of the action as ‘Bento’ and the middle-aged man who narrates the action as ‘the narrator’.*

So, from here on in, I’m going to assume that you know that Bento Santiago does indeed marry his childhood friend Capitu; that they have a son, Ezequiel; that their conjugal happiness is ruptured by the drowning of their friend Escobar; that Bento, suspecting his wife of infidelity, concludes that Escobar was Ezequiel’s true father; that, after contemplating first suicide and then murder, he sends his wife and son away to Europe. If we take his narrative at face value, the bitter solitude of Bento’s middle-age—his metamorphosis into ‘Dom Casmurro’—is thus explained by the crushing disillusionment caused by his wife’s betrayal; in this light, the novel appears as a mixture of prosecution of Capitu’s misconduct, justification of Bento’s response to it, and failed attempt to come to terms with the past, to make sense of an enigma that proves unsolvable. But even as this narrative takes shape, a counter-narrative also begins to emerge: that the narrator is mistaken or even lying; that Capitu was faithful all along; that it is Bento’s obsessive jealousy, bordering on madness, which leads him to turn his family away and condemn himself to the torture of living alone and unloved. This counter-narrative exposes the narrator as an unreliable figure whose cruel delusions and/or lies (they may not be distinguishable) are revealed when the reader treats the text sceptically and critically. Once these competing narratives are apparent, the novel then seems to revolve around the question of Capitu’s fidelity, with the reader tasked with choosing between two possible conclusions in the absence of a definitive authorial statement. I write ‘seems’ because Machado is not content with elementary ambiguities. Other interpretations are possible; it’s also possible that the whole question isn’t that important anyway.

It was fascinating to learn that for the first half of the twentieth century, Brazilian critics who wrote about Dom Casmurro accepted the narrator’s account almost without question; the idea that Capitu’s alleged infidelity might have been an error or an outright fabrication on the part of a pathologically jealous husband does not appear to have been given much consideration until the publication in 1960 of Helen Caldwell’s study The Brazilian Othello of Machado de Assis. Caldwell, the novel’s first English translator, proposed that Capitu, like Shakespeare’s Desdemona, is the innocent victim of her husband’s paranoia and that Bento is a kind of hybrid Othello/Iago figure who deceives himself with his overactive imagination.** For all its importance in the history of Machado studies, however, I found Caldwell’s book a chore to get through; not only does it exasperatingly refer to fictional characters using the past tense, as if they were real historical personages, it also distorts the novel by stressing one aspect of it to the exclusion of all else. In this, her tunnel vision is as restricted as that of R.L. Scott-Buccleuch, her successor as translator; it scarcely matters whether one calls Dom Casmurro a story ‘about’ jealousy (Caldwell) or adultery (Scott-Buccleuch), for in both cases so much of what makes it such a rewarding yet bewildering work is missed. In both cases, the focal point is the same, yet it is not clear to me whether the novel has a focal point at all.

The manner in which the narrator reveals the ‘truth’ about Capitu and Escobar is so peculiarly indirect, gradual and muddled that it might with equal plausibility be read as a sign of narratorial guile or guilelessness. Certain events prior to the marriage might be taken as foreshadows of what is later revealed (e.g., Capitu’s cunning in concealing their romance; José Dias’s insinuation that she is waiting for a local beau to marry her; the look she exchanges with a passing dandy on horseback), but the first hint of adultery that I detected is when Escobar changes some money that Capitu has saved into pounds sterling. When Capitu tells her husband what she has done, he is surprised, but apparently not troubled; readers, meanwhile, may be troubled by Capitu’s capacity for secret dealings with Escobar, who even visits her at home while Bento is out. The narrator does nothing to tip the wink here; there’s nothing to the effect of ‘this is where I first began to suspect’ or ‘this is perhaps where I should have begun to suspect’; he maintains a façade of innocence even though he is writing years after the event, in full knowledge of its significance to what he later discloses. In the next few chapters, there are further intimations that all is not well: Ezequiel’s remarkable ability to imitate Escobar, which Capitu condemns as a bad habit; Escobar’s presence at Bento’s front door when Bento returns from the opera unexpectedly; Dona Glória’s coolness towards her daughter-in-law and grandson. Again, the narrator gives little sense of Bento being aware at the time of an affair between his wife and best friend, nor does he make it clear to the reader that this is what he now thinks took place; while there is a reference in a conversation with Capitu to doubts croaking like frogs inside him, Bento does not accuse Capitu of anything at this point; the doubts appear to concern his mother’s odd behaviour. When, after Escobar’s death, Capitu gazes at his body in a way that suggests a widow looking upon the corpse of her husband, Bento suddenly suspects he has been betrayed, but even here, the narrator is not explicit about this suspicion. When Bento delivers Escobar’s eulogy, he struggles to hide ‘the truth’ from the mourners, but the narrator does not state plainly what that truth is. Seeking mental clarity as he ruminates in the carriage on the way back from the funeral, Bento concludes that he has been blinded by his ‘old passion’, but here, again, the narrator is unclear: does he mean the passion of his love or the passion of his jealousy? Is this the point at which the scales fall from the deceived husband’s eyes, allowing him to perceive Capitu’s faithlessness? Or does he (temporarily) decide that his natural jealousy has led him to read too much into a single look? Nothing is stated without ambiguity, which makes a mockery of the narrator’s claim to present things in a ‘logical, deductive order’. Indeed, before Escobar’s death, readers may be misdirected into believing that it is Bento who will commit adultery when he develops an attraction to Escobar’s wife Sancha. In any case, Capitu’s mysterious gaze at the dead man, however suggestive, is not conclusive; the crisis is postponed until Bento notices the growing physical resemblance between Ezequiel and Escobar. It is this resemblance that apparently convinces Bento once and for all that Ezequiel is not his son; it is when he relates this realisation in Chapter 132 that the narrator finally uses entirely unambiguous language to refer to the affair (‘my friend, my wife’s lover, Escobar’). But even as the narrative of a wife’s adultery and betrayal, hitherto only alluded to in semi-obscure fashion, is at last fully unveiled, Machado is also baring the counter-narrative of a husband’s jealousy and paranoia.

The main evidence that Bento for his wife’s infidelity is Ezequiel’s physical resemblance to Escobar—a resemblance that only becomes fully apparent to Bento after Escobar’s death, when Capitu herself draws his attention to it. Later, just as Bento’s resolve to separate from his wife and child is wavering, Ezequiel’s entrance enables Bento to quickly compare the boy with a picture of Escobar; this, together with a look on Capitu’s face that he interprets as a confession, are enough to remove all doubt. As prime evidence, this is not convincing, especially as one party is dead and only his image can serve as point of comparison. The narrator reminds readers of another striking resemblance between a living person and the image of a deceased one: Capitu’s resemblance to the portrait of Sancha’s mother. Though Bento recalls this purely coincidental resemblance just before Capitu agrees to a separation, the recollection does not prompt him to question his certainty that he has been betrayed; indeed, when he continues to brood on the past, he re-evaluates his memories, reading sinister cunning into episodes between his wife and Escobar where none had previously been apparent. ‘Now I remembered everything that at the time had seemed to be nothing’, writes the narrator, which is almost an invitation to the reader to ask whether that ‘everything’ is anything but a distortion of the past to make it conform to an idea.

The two narratives—the one of Capitu’s adultery and the one of Bento’s delusions—are, in their strongest forms, irreconcilable. Both cannot be true: either Ezequiel is Bento’s son or he is not. Readers are not necessarily limited to choosing between these two narratives, however. Weaker variations, unmentioned by the narrator, might also be possible: that Capitu remains faithful, but secretly desires Escobar (just as Bento conceives a momentary lust for Sancha, which he does not act on); that Ezequiel is Escobar’s son after all, but is the result of a brief dalliance rather than a prolonged affair; that Ezequiel is neither Bento’s nor Escobar’s son; that Bento, not Capitu, is the unfaithful one (with Sancha, or with another woman) and his accusations are just designed to conceal the truth. There isn’t any evidence to support these hypotheses, but if we decide that the narrator is utterly unreliable, to what extent are we bound to the evidence of his narrative? If nothing is knowable, then is one version of events as good as another? One particularly wild idea I entertained is that, rather than abandoning his plans to kill his wife and child, Bento really does go through with them; the whole story of their exile in Europe is a madman’s rewriting of history; the replica of his childhood home that he builds in middle-age exists only in his mind. Here’s another version: he murders his wife and child in cold blood, then concocts the story of sending them to Europe as a devious explanation of their absence. Or perhaps he just kills one of them and then gets the other out of the way by exiling them. I’m not arguing that any of these hypotheses ought to be taken seriously so much as suggesting that they can’t be entirely discounted; if we accept that much, then not only does the choice between a faithless Capitu and a deluded Bento no longer seem so starkly binary, but it also seems of diminished importance to our understanding of the novel.

There is another narrative for which there is rather more textual evidence: that Bento, perhaps without knowing it, is in love with his best friend. It’s always worth reminding ourselves, of course, that what might appear homoerotic to us as modern readers may not have been understood as such by readers and authors in the past; even today, there are societies in which close same-sex friendships can involve a high degree of physical intimacy that is not remotely sexual. There need not be anything erotic in the kind of embrace in which Bento and Escobar are observed in Chapter 94—but then what are we to make of the disapproval this gesture earns from the priest and other seminarians who witness it? The priest says that it is immodest; Escobar remarks that this is a rebuke made out of envy; he secretly grasps Bento’s hand and squeezes it so firmly that the narrator imagines that he can still feel it. Elsewhere, the homoeroticism is mixed up with other aspects of sexuality: voyeurism, jealousy, envy, egotism, displaced desire. The dream that the narrator recounts in Chapter 63 is a precursor to an incident that actually happens later on; in the dream, Capitu provokes Bento’s jealousy by chatting to a local beau, which anticipates the later episode in Chapters 71-73, in which Bento is made jealous by Capitu’s exchange of glances with just such a local beau. However, whereas in the later episode, it is Capitu who watches the parade of young men visiting their sweethearts while Bento looks up at her, in the dream, it is Bento who is looking at the young men. The later episode in begins with Escobar leaving Bento’s house; Capitu (who does not yet know Escobar) secretly watches the whole of their affectionate parting from her window and deduces that they must be very close friends. What Bento does not tell her is that he is disappointed when Escobar does not turn back to leave him with one last glance; it is while he is in this state of disappointment, looking up at Capitu, that he notices the lingering shared look between Capitu and one of the passing beaux—an elegant figure who is unnamed, but whose face is ‘not unfamiliar’ to Bento (recognised from the dream, perhaps?). So much is going on here. Both Capitu and Escobar disappoint/anger Bento by not making him the focus of their vision; the sense of betrayal that leaves Bento with a ‘burning heart’ is a double betrayal. The beau passes by just after Bento tells Capitu his friend’s name; this identification of Escobar with the young rider drops a hint of the future adultery storyline (a hint underscored by a reference to Othello). Is the narrator signalling to readers that it was a mistake for Bento to have been so upset by Capitu’s exchange of looks with the horseman when the real cause for concern should have been her voyeuristic observation of Escobar? Is there, at the same time, a touch of jealousy in Capitu’s behaviour? Does she recognise in Escobar a potential romantic rival?

Desires are similarly entangled in Chapter 118, when Bento mulls over the possibility of an affair with Sancha. It is Sancha’s ‘warm and imperious’ eyes that raise this possibility in Bento’s mind; she is excited by the idea of a joint trip to Europe. There is already something odd about the closeness of these two couples—a whiff of the perverse, even (the husbands plan an even closer union by pairing off their children). Might a sojourn in decadent old Europe provide opportunities for further intimacies? Strikingly, both Sancha’s and Bento’s eyes assume in this passage the quality of independent objects that move about the room and follow each other; when Machado writes ‘the four of them stopped and faced each other’, he means the two pairs of eyes belonging to Sancha and Bento, but the number also calls to mind the four members of the Bento-Capitu-Escobar-Sancha quartet. Just as Bento is contemplating this new attraction to Sancha, her husband announces that he is going to swim in the sea the next morning, though he knows it will be rough (fatally so, as it turns out). Escobar slaps his chest in a display of masculine strength and invites Bento to feel his arms, which Bento does, in an extraordinary act of substitution, ‘as if they were Sancha’s’. But what is being substituted here? Is Bento, denied the pleasure of feeling Sancha’s arms, using Escobar’s as an erotic substitute, or is the narrator, unable to admit to experiencing pleasure at feeling Escobar’s arms, using Sancha’s as a narrative substitute? Mingled with this desire (whether for Escobar or for Sancha or for both of them) is a feeling of envy, for Escobar’s arms are thicker and stronger than his own. As he leaves, Bento again tries to communicate to Sancha with his eyes; her response is to squeeze his hand hard, which recalls the similar scene between Bento and Escobar in the seminary (the words ‘modesty’ and ‘gesture’ serve as verbal echoes). Escobar’s exhibition of virility—so much in contrast to the slim, restless seminarist described in Chapter 56—raises further questions. Is he trying to intimidate Bento, to warn him off after noticing the interaction with his wife? Or is he offering himself as an alternative object of desire, reminding Bento of where his affections ought to lie? This open display and admiration of arms among the husbands is in pointed contrast to their wish that their wives wear long sleeves at balls so as not to arouse other men.***

The questions of Ezequiel’s paternity and Bento’s romantic affections are expressions of an anxiety about masculinity evident throughout the novel. Bento is sometimes presented as not quite ‘manly’: he is terrified of horses and mules as a child (a pointed contrast to the elegant rider with whom he suspects Capitu of flirting); his lover and then wife is, as the narrator writes, ‘more of a of a woman that I was a man’ (Chapter 31); he is inferior to Escobar in strength and swimming prowess; he is late (compared to Escobar) in producing an heir. Ezequiel himself is, as a child, far bolder than Bento, being prepared to chase away stray dogs and interested in violence and soldiering; the signs of an enterprising nature that Escobar sees in him might be taken as a sign of kinship. How significant is it that, even before his friend’s death, Bento keeps a picture of Escobar next to one of his mother at his beachside house? In the Matacavalos house (and in the later replica of it), Dona Glória’s picture is situated next to one of her husband—the unremembered father who, by dying, leaves José Dias and Uncle Cosme (neither of them conventional models of masculine virility) to serve as the two main male influences in his son’s upbringing. Does Escobar represent for Bento an ideal of manhood and paternity unavailable to him as a child? Does Escobar’s death bring Bento’s sense of masculinity to such a point of crisis that he can only resolve it by enacting the unlikely role of a stern avenging cuckold à la Othello? Perhaps it is little wonder that Machado’s early (male) critics took the narrator’s account largely at face value; had they taken the portrait of the protagonist as at all representative of respectable Brazilian masculinity, they might not have welcomed the questions they would then have had to face. If the narrator’s account goes unquestioned or if the difficulties it raises are too easily resolved, other problems (socio-political, psychological, philosophical, literary) either then do not arise or appear less prominent. This applies as well if we simplify the book into a tale of an honest wife wronged by a cruelly paranoid husband. This, it seems to me, is the role that Capitu’s fidelity or otherwise plays in Machado’s design: not as the central question to be definitively answered one way or another (it’s just fiction, after all), but as a catalyst for other, more interesting questions and considerations—for which this post has no room to examine.

* Some critics simply use ‘Dom Casmurro’ to refer to the narrator, while using Bento for the protagonist (and sometimes also Bentinho for his juvenile incarnation). This doesn’t seem satisfactory to me; I don’t think it’s helpful either to elide all distinction between the narrator and ‘Dom Casmurro’ (which is a nickname coined by someone else that the narrator adopts as a title) or to make the distinction between ‘Dom Casmurro’ and ‘Bento’ too clear.

** Brief accounts of Dom Casmurro’s critical history can be found in Paul B. Dixon’s Retired Dreams: Dom Casmurro, Myth and Modernity (1989) and James R. Krause’s Translation and the Reception and Influence of Latin-American Literature in the United States (2010).

*** There are precedents for the open representation of same-sex desire in 19th century Brazilian literature, as noted by John Gledson in his chapter ‘Machado de Assis and Graciliano Ramos: Speculations on Sex and Sexuality’ in Lusosex: Gender and Sexuality in the Portuguese-Speaking World (2002), ed. Susan Canty Quinlan and Fernando Arenas, pp. 12-34. Machado sometimes writes about sexual matters in Dom Casmurro with a surprising degree of candour—though with just enough ironic coyness to avoid censure from guardians of morality; see, for example, the veiled but unmistakable reference to wet dreams and masturbation in Chapter 58.

When I looked at two of the available translations of Dom Casmurro in my previous post, I suggested that the differences between them might be regarded as expressions of different answers to the question posed above. R.L. Scott-Buccleuch, in his rather cursory introduction, is quite clear on the matter, stating that the theme of Machado’s novel is… well, no, I’m not going to say what that theme is just yet, as it would mean giving away too much of the plot; that can wait for another post. A now out-of-print incarnation of the translation was furiously denounced when it was discovered that whole chapters had been omitted without acknowledgement or explanation; it seems impossible to conclude why this was done, since both Scott-Buccleuch and his previous publisher, Penguin, appear to have refrained from commenting on the controversy, but it is tempting, nonetheless, to consider it no coincidence that the surreptitiously excised material is, on the face of it, largely extraneous to what Scott-Buccleuch identifies as the novel’s theme. The theme places Dom Casmurro within a tradition of 19th-century fiction well-known to readers of European and North American literature, who might not have the faintest notion of the literature of Brazil; viewed through this lens, the novel might even appear reassuringly familiar to such readers. No need to worry, then, if you know nothing of the Paraguayan War of 1864-1870, of the intricacies of Brazil’s slave economy, of the history of its royal family, of the peculiarities of its social structure, of the geography of Rio de Janeiro, because none of this is important to Machado de Assis, whose only concern was to write ‘a tale of suburban life’ whose setting ‘might well be a variation of Paris, Vienna, or London’. But Dom Casmurro will not stay confined within such a neat little box.

Before I consider how Gledson’s reading of the novel might have led him to produce such a different translation, I had better introduce it a bit more fully than I did in my previous book; perhaps this will give some idea of the inadequacy of Scott-Buccleuch’s characterization of it. The narrator is Bento Santiago, a middle-aged man living alone (apart from a single servant) in Rio de Janeiro towards the end of the 19th century, in a house that is an exact replica of his now-demolished childhood home. Bored in his uneventful seclusion, he decides to write a volume of memoirs, selecting as a title his nickname, Dom Casmurro.* The story Bento tells begins in 1857, when he was fifteen and in love with his next-door neighbour, Capitu. The young lovers are divided by class, for while Bento is the son of a rich, slave-owning widow, Capitu’s father, Pádua, is a civil servant with a modest income, who bought his house with a share of a winning lottery ticket. The romance is threatened by a solemn promise made before Bento was born: after losing one son, his mother, Dona Glória, had promised God that her second, should he be allowed to live, would become a priest. The naïve, passionate yet also passive Bento and the far more practical Capitu strive to devise a plan to avoid his being sent to the seminary. Other important characters in this story include José Dias, an obsequious devotee of homeopathy who lives with Bento’s family, dependent on their generosity; Uncle Cosme, a corpulent lawyer with a love of cards and backgammon; Cousin Justina, a sharp-tongued widow; Capitu’s best friend Sancha; and Bento’s enterprising best friend Escobar.

So much for the plot and the characters. What makes a large portion of the book so enjoyable is the beguilingly Shandean narrator, who indulges in digressions, addresses his readers directly, peppers the text with ellipses (much as Tristram Shandy peppers his account with dashes), drops in abundant literary and historical allusions, claims forgetfulness, makes false starts, lays bare the mechanics of writing. Adolescent emotional excesses, religious hypocrisy, the petty absurdities of a class-bound, priest-riddled society: these are relayed with a wry irony that stops well short of scorn, so that the tone is generally polished and amusing, sweet yet ever so lightly cynical, with just enough eccentricity and playfulness to avoid being insipid. Here, for example, is Bento on a friend of the family, who has just been promoted to an important position in the Church, being congratulated by Capitu:

Father Cabral was in the first flush of glory, when the slightest congratulations seem like laudatory odes. The time comes when those who have been honored take this praise for granted, and accept it without acknowledgement, blankfaced. The excitement of the first moment is best; that state of mind which sees the bending of a tree in the wind as a personal homage from the world’s flora brings more delicate, more intimate sensations than any other. Cabral listened to Capitu’s words with infinite pleasure.

The image itself is hilarious enough; what makes it funnier is that the worldly pride of this elderly priest is described in the heady language of young love’s first stirrings, the sensation of a first kiss, at once carnal and innocent—the kind of language that Bento has already applied to himself, so that the humour works both ways. But not everything is as delightful as this kind of genial slyness. Slavery, poverty, avarice, sickness, death: at first, they seem peripheral, but their presence becomes more insistent. There are oddities of tone in Bento’s narration, strange fantasies, lacunae, evasions, which may seem merely eccentric early on, but which begin to promise a darker turn… and then, well past the half-way mark, it all goes completely haywire.

What does Gledson make of all this? In stark contrast to Scott-Buccleuch, the Paraguayan War, the slave economy, the politics and society of the Brazilian empire, and the geography of Rio de Janeiro are all very much relevant to his view of the nature of the book; accordingly, his translation is buttressed by detailed footnotes and a substantial introduction, as well as an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Contextual knowledge is deemed necessary, because Machado de Assis is, in Gledson’s eyes, essentially a realist author of works of trenchant social criticism—a surprising position, you might think, given Dom Casmurro’s narrowly subjective viewpoint, its formal tricksiness, its lack of direct political engagement (Bento professes a distaste for politics). In his introduction, Gledson points to Machado’s rejection of deterministic Naturalism as a spur to his turn away from the omniscient third-person narrator in favour of intricate experiments in narration—not as a repudiation of realism, but as a move towards a form of realism that embraces the narrator, ‘thoroughly grounded in his own physical and temporal environment’. The informed reader, attentive to the gaps between the narrator’s discourse and the author’s, is not restricted to the narrator’s view of that physical and temporal environment; the realistic social critique becomes visible once the reader realizes that the subjective experience of Bento Santiago (and of Bentinho and Dom Casmurro) is part of a much broader picture that includes slavery, gender roles, social inequalities, hypocrisy, religious cant, obsession with money, etc.

This is not the Machado de Assis fatuously saluted by Harold Bloom as ‘the supreme black literary artist to date’, whose ironical genius is blessedly autonomous ‘in regard to time and place, politics and religion’.** Neither is it the proto-modernist or proto-post-modernist Machado, the subtle rhetorician and metafictional trickster who anticipated Borges, Carpentier, Cortázar. When Alfred Mac Adam, one of Gledson’s critical opponents, cites Trollope’s He Knew He Was Right (1868-9) as a genuine realist novel—long, bursting with subplots and supporting characters, directly tackling pressing social questions, conveying ‘an overwhelming sense of totality’—as a contrast to Dom Casmurro, it might be seen as a somewhat facile ploy (look at these two completely different books and note how completely different they are), but it stresses the major problem for proponents of the realist Machado: if Dom Casmurro does indeed present a view of society, then why is it ‘so oblique as to be obtuse’?*** Much of the case for Machado as a social critic depends on allegory and analogy, some of which is so subtle and allusive that its recognition is scarcely possible without scholarly exegesis and the determined rooting-out of covert authorial intentions; hence the necessary apparatus of foreword, footnotes and afterword, without which the force and extent of the social critique might not be apparent to ordinary readers.

There is a problem, though, for those who would deny that Machado portrays a society, for while there is little in the way of thick description, there is an abundance of small, precise detail: names of streets, churches, suburbs; information about jobs and social status; the particulars of Dona Glória’s income; the names of even very minor characters. If Dom Casmurro is a text about language, an anti-realist exercise in formal experimentation uninterested in representing the world, why this superfluous profusion? Is it not a distraction? Not only that, but the allusiveness of the novel is not solely inter-textual; some of the references seem to have an extra-textual, social significance that is hard to dismiss, just as it is hard to dismiss the presence of pointed political allegory. The world keeps peeping through. Readings that are oblique are not necessarily unconvincing—but further discussion will have to wait for other posts, which will include information about the plot that readers who have not read Dom Casmurro may want to avoid. I’m not usually bothered by spoilers, as I don’t tend to read books primarily for their plots, but in this case I’m glad I didn’t know what lay ahead of me as I read, as it meant that Machado’s formal and conceptual brilliance struck me with all the more power.

* ‘Casmurro’ has a range of meanings that includes taciturn and stubborn. The character of the narrator has, in effect, three names that can be identified with particular periods of his life: Bentinho as a child and adolescent; Bento as a young man; and Dom Casmurro as a man in his fifties. For the sake of convenience, I will generally stick to using Bento. Although it might seem natural to use the name associated with the ‘author’ of the text (within the fiction, that is), to do so would be to give the book an inappropriate emphasis, for reasons that will be evident to anyone who has read it. No choice is completely satisfactory—and that includes the surname, Santiago—but Bento seems to me the least objectionable.

** This is from Bloom’s 2002 book Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds, quoted on p. 150 of James R. Krause’s doctoral dissertation, available to read here.

*** See Mac Adam, Alfred (1999). The Rhetoric of Jealousy: Dom Casmurro. Hispanic Review, Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 51-62.

It was wonderful to read Dom Casmurro—wonderful to be charmed by its urbane, relaxed irony, and then thrilled by the audacious surprises it springs towards the end, when early impressions of the book are gleefully torn asunder. Bento Santiago, a solitary, middle-aged lawyer, recalls a youthful romance with his next-door neighbour, the practical and clear-sighted Capitu. The story recounts the lovers’ struggles against what appears to be the main obstacle to their happiness: a promise made to God by the boy’s pious mother that he be sent to a seminary and ordained as a priest. The mature Bento, who claims to be writing partly in order to cure his boredom, is a delightful and digressive narrator whose teasing sophistication undercuts the display of sentimental nostalgia without demolishing it. For much of its length, the novel is like a pleasant white wine sipped on a fine summer’s evening, with a few hints of bitterness (the presence of slavery, the dominance of the church, Bento’s own jealousy) to ward off excessive sweetness; but the bitter notes become more prominent, until they suddenly become overwhelming, and it’s no longer wine you’re drinking, but vinegar.

My satisfaction upon finishing the book was short-lived, however, for a few hours later I made the horrifying discovery that the translator, R.L. Scott-Buccleuch, had omitted nine chapters without explanation, provoking a storm of scholarly outrage; without those nine chapters, could I actually claim to have read the novel? I researched and weighed up the other options: a translation by Helen Caldwell from 1953 and one from 1997 by John Gledson. Commentary on Caldwell seemed to agree that her version was respectable but somewhat stodgy, so I ordered a copy of the Gledson and read it two weeks after I had finished Scott-Buccleuch. My appreciation for Machado’s brilliance was deepened by reading Gledson’s superior rendering; in this post I want to explore some of the reasons for its success.

As I read Gledson’s version one thing puzzled me: I did not seem to be encountering anything new and unfamiliar in terms of the book’s contents. I checked Scott-Buccleuch again; the supposedly missing chapters were, in fact, all present, so what was going on? The publication history offered a clue: the translation was first published by Peter Owen in 1992, before appearing under the Penguin Classics label in 1994; the copy I had was from 2016 (Peter Owen again), with a note to say that it was complete and unabridged. Had Scott-Buccleuch newly translated the previously missing material and silently re-inserted it? His introduction offers no information, and is completely silent on the controversy surrounding the earlier version. What is not clear to me yet is whether the 1992 version is complete; all the criticisms I’ve read of his earlier omissions refer to the Penguin translation. I would have to check a copy of the 1992 edition to be sure.

The chapters that Scott-Buccleuch excised are of little consequence for the plot—but conventional plot-based storytelling is hardly Machado’s chief concern. Their importance relates primarily to our understanding of the nature of the narrative. A religious poem composed by one of Bento’s contemporaries; an attempted sonnet by Bento himself, of which only the first and last lines are completed; a sexual fantasy; reflections on the narrator’s poor memory, on his reading habits, on nostalgia: all these things contribute to our sense of Machado’s authorial cunning and enrich our sense of the novel’s multiple ambiguities. So why cut them out? The chapters in Dom Casmurro are notably short, some of them consisting of a single brief paragraph; the abridgement would have had a negligible page-reducing effect. It does not seem to have been merely an error, as, from what I understand, not all of these chapters were excised completely; a few sentences were retained as if to paper over the cracks and disguise the act of removal. As neither Penguin nor Scott-Buccleuch appear to have explained themselves or responded to the criticism, motivations must remain mysterious for the present.

This murky affair aside, however, Gledson’s translation is clearly preferable. Gledson himself has pointed out his predecessor’s laziness and disregard for social specificity; a telling example is provided by Scott-Buccleuch’s rendering of the term ‘agregado’ as a ‘friend of the family’. The character to whom this applies, José Dias, is someone who lives with Bento’s family and depends on them financially; Gledson, by translating ‘agregado’ as ‘dependent’, gives a sense of José Dias’s particular social status that Scott-Buccleuch misses. Scott-Buccleuch’s slapdash imprecision is very much apparent if we compare the opening paragraph of each translation. Scott-Buccleuch’s is first, followed by Gledson’s.

One evening on my way home to Engenho Novo from town I met a young fellow on the Central Line train. He lived in the neighbourhood, and I knew him vaguely by sight. He greeted me, sat down beside me, talked about one thing and another and ended up reciting poetry. The journey was short, and his verses may not have been altogether bad. But it happened that I was tired, and I dozed off once or twice, causing him to break off his reading and put his verses back in his pocket.

One evening just lately, as I was coming back from town to Engenho Novo on the Central line train, I met a young man from this neighborhood, whom I know by sight: enough to raise my hat to him. He greeted me, sat down next to me, started talking about the moon and ministerial comings and goings, and ended up reciting some of his verses. The journey was short, and it may be that the verses were not entirely bad. But it so happened that I was tired, and closed my eyes three or four times; enough for him to interrupt the reading and put his poems back in his pocket.

Given Scott-Buccleuch’s demonstrated willingness to omit whole chapters, it should not be surprising to find less conspicuous omissions. Gledson retains the idea of the social gesture of raising one’s hat in greeting, a gesture appropriate to somebody the narrator often sees but doesn’t know very well; I don’t know Portuguese, but I would guess it corresponds to ‘que eu conheço de vista e de chapéu’ in Machado’s original. Scott-Buccleuch, replacing a gesture with an adverb, implicates by its placement not only the degree of acquaintance between the two men, but also the act of recognition, as if Bento were not able to immediately identify the young man’s face—a slightly different idea. Gledson also retains the twin subjects of the young man’s prattle (‘da Lua e dos ministros’), an intriguing pairing that might cause us to ponder the possibility of a connection between them. Is the young man a bit cracked? Is Bento having fun at his expense? Or are the moon and ministers simply the two things that stuck in Bento’s attention? Just this little phrase opens up a range of possibilities denied the reader by Scott-Buccleuch’s flavourless ‘one thing and another’. In Scott-Buccleuch, Bento dozes off once or twice; in Gledson, he closes his eyes three or four times; Machado’s ‘fechei os olhos três ou quatro vezes’ makes it pretty clear who is more accurate here. Fidelity to the original is not the only measure of a translation’s success, of course, and the difference in Bento’s reaction to the unsolicited poetry recital may seem minor; nonetheless, dozing off is a rather more obviously insulting action than closing one’s eyes, and so it creates a different impression of the offence the young man takes at Bento’s tiredness. The change from ‘três ou quatro vezes’ to ‘once or twice’ is hard to explain, and is not the only numerical inconsistency in Scott-Buccleuch; I can only assume that it is the result of a simple error that he gives José Dias’s age as about fifty-two, rather than fifty-five.

One very noticeable difference between the two translations is their treatment of the snippets of dialogue given to the slaves who appear from time to time. Scott-Buccleuch, perhaps out of a desire to avoid degrading minstrelsy, reduces the caricatured servility and makes no attempt to reproduce Machado’s colloquialisms:

Outside, a black man, who had for some time been selling cocadas, coconut sweetmeats, stopped in front of us and said, ‘Senhorita, do you want some cocadas today?’

‘No,’ replied Capitu.

‘They’re very good.’

‘Go away,’ she said but not harshly.

‘Give me two,’ I said, reaching down to receive a couple.

Gledson, I think correctly, decides against this tidying up, and also sticks closer to Machado’s layout of the text:

We had gone over to the window; a black who for some time had been hawking coconut sweets, stopped in the street opposite and asked:

“Missy want coconut today?”

“No,” said Capitu.

“Coconut good.”

“Go away,” she replied, but not harshly.

“Give some here!” said I, putting my hand down to take two.

It is not stated whether this cocada seller is a slave, though he is portrayed in the same uncomplaining, deferential way that other minor characters who are definitely slaves are portrayed. Corrosive, fraudulent nostalgia, including for the era of slavery (finally abolished in Brazil in 1888, when Bento would have been in his mid-forties), is one of the main themes of the book, which is extremely attentive to the social status of its characters; the stereotyped, racist presentation of dialogue and character by the narrator is an indicator of his class, which profits from slavery. Machado does not simply indict his narrator as an individual, he indicts the whole social structure that he represents; some of the force of that indictment is lost if the racism and class dominance that characterized that social structure are down-played.* It may also make a difference whether the cocada seller, whom Bento calls ‘um preto’ in the Portuguese, is referred to as ‘a black man’ or as ‘a black’—although the precise nature of that difference is something beyond my ability to judge. Neither rendering of the word conveys the complex history of racial categorisation in Brazil, with its range of labels for different skin tones (something of which I am only dimly aware); probably only a footnote—or, better, a paragraph or two in the introduction—would have sufficed in that regard.** I am left wondering whether Scott-Buccleuch, by changing ‘black’ into an adjective and inserting ‘man’, removes the expression of a dehumanising classifying element that was integral to the society the novel portrays, or whether Gledson, by hewing more closely to the original wording, neglects the cultural difference that might lead a modern anglophone reader to experience a kind of mental jolt on encountering what would have been, in context, a matter-of-fact term. Perhaps the truth is something else entirely. It does seem clearly unsatisfactory, though, when Scott-Buccleuch at another point translates ‘um preto’ as ‘a servant’, which disguises the reality of slavery interwoven throughout the ostensibly wistful reminiscences of an adolescent romance. The choices made by these two translators may well represent different answers to the question: just what kind of a novel is Dom Casmurro? I will begin to explore this question in a separate post, but I will say now that I don’t believe it’s a question that can ever be satisfactorily answered.

* There is also the possibility that the cocada seller’s mode of speech is a deliberate display for the benefit of his intended customers, i.e. that he is speaking in the way that he supposes free white people with money would expect of him. Interestingly, in Caldwell’s translation of this passage, Capitu and Bento too become more colloquial (“Go ’way,” and “Give ’em here!”), as if they alter their speech when addressing someone far lower down the social hierarchy. Caldwell translates ‘um preto’ as ‘a Negro pedlar’, which seems to me like an imposition of terminology from a North American context.

** It’s a telling indicator of the difference between the two translations that while Scott-Buccleuch dispenses with footnotes altogether (not necessarily a matter wholly within his control, of course), Gledson’s, though lacking in this instance, are copious and generally illuminating.

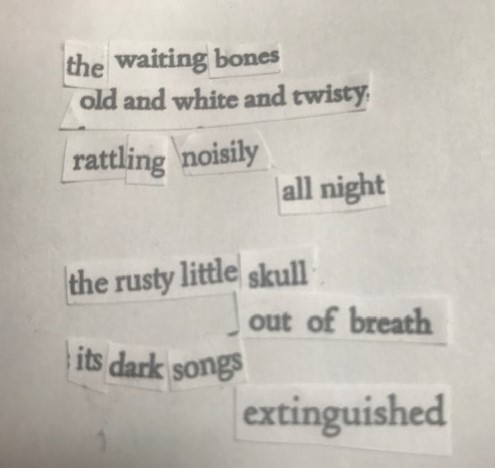

1.

the waiting bones

old and white and twisty

rattling noisily

all night

the rusty little skull

out of breath

its dark songs

extinguished

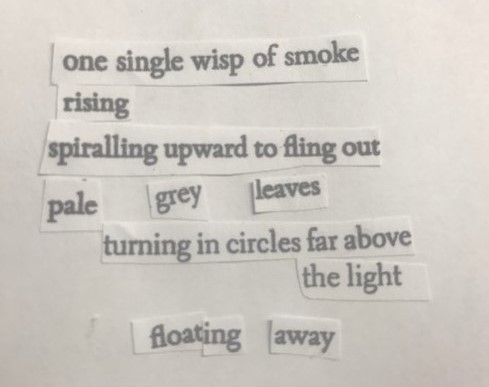

2.

one single wisp of smoke

rising

spiralling upward to fling out

pale grey leaves

turning in circles far above

the light

floating away

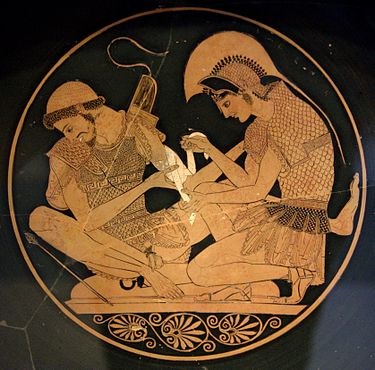

This piece grew out of an assignment for my PGCE, which involved writing a short story and reading it to a class of students. As my Year 7 class happened to be studying Greek myths, I thought it would be convenient to base my story on one of those myths, using the audio tales recorded by Daniel Morden and Hugh Lupton for Cambridge University as a model. I chose the myth of Lycaon because Morden and Lupton’s version is rather short, and so left me with plenty of scope for embellishment. The horrific elements would be bound to appeal to a significant proportion of my students, yet they might also be a little too horrific for some. In order to offset this, I decided to leaven the horror with some broad comedy involving pizzas with pineapple and sweet potato toppings. This may have been a mistake, for while the students enjoyed the story, some of them found the tonal mixture too jarring; they tended to prefer either the horror or the comedy. In the revision that appears below, I have removed the broadest comic elements (no more pizza), while retaining a few slightly less broad gags.

In the city of Arcadia, such things as kindness and good deeds were unknown—only greed, dishonesty and hatred. The people lied and stole and murdered without shame. Strangers would be robbed and buried alive. Neighbouring cities would be surprised at night, looted and set on fire. The old and the sick knew no support or protection there, only mockery and ill-treatment. Every outrage the citizens committed would be accompanied by howls of laughter, as if to kill, to maim, to steal were great jokes. Among this rabble of villains, no-one was fouler or more villainous than the king, wolf-hearted Lycaon, and his fifty detestable sons, whose cruelty knew no bounds. Cries of pain and anguish, coming from the palace, echoed ceaselessly through the bone-littered streets. The walls of the royal treasuries bulged and cracked with stolen gold; the granaries overflowed with stolen grain. The air hung heavy with the acrid stench of blood, which in Arcadia was judged the sweetest smell of all.

Reports were not slow in travelling. They travelled far, as far even as Olympos, abode of the gods, whose ruler, mighty Zeus, the cloud-compeller, received the news with a stern frown. Such acts, he thought, were not unknown among mortals—they were not unknown among gods—but could he permit them to continue so openly, so impiously?

“These Arcadian dogs insult me!” he complained to his queen, ox-eyed Hera, who listened with a serene smile. “Have they no heed of my divine wrath? Have they forgotten their dues towards me?”

And great Zeus shuddered in disgust, and as he shuddered, there were earthquakes and landslides below, and many people died.

“Great king,” said Hera, “they cannot pay their dues if you bury them all under rocks”.

“Not all, dearest queen,” Zeus replied gloomily. “Not all”.

“Be sparing in your divine wrath, my love. Do not act in haste. Go to Arcadia yourself. See with your own eyes their crimes, that you may better judge them. If you punish these Arcadians, let their punishment be fitting. Let it be known that the work is yours.”

“What punishment can hope to fit such wickedness?”

“Mighty Zeus,” said his queen, “there is no mind that can match yours for perfect wisdom.”

The terror-bringing mouth of the king of the gods opened to speak, and stayed open, and then shut, without issuing a sound. And then it opened again, but still there was no sound, and then it shut once more. The stern brows of all-knowing Zeus knitted into a frown.

Ox-eyed Hera sighed, and smiled another serene smile, and then she gently bent her beauteous head closer to her husband’s ear. And as he listened, the mouth of the king of the gods was soon smiling too.

The next evening, a stranger, hobbling along the streets of bone-paved Arcadia, came to the immense gates of the royal palace and requested entrance. He was an old man, dressed in torn and dirty rags, whose dirty, bedraggled beard reached almost to his feet. His skin was a sickly shade of pale green spattered with blotches of purple; his few teeth quivered as he spoke; his eyes were milky and distant. The breath that came from his mouth was rank. Only the sternness of his brow gave any hint that this filthy, feeble old man was not quite what he seemed.

The guards laughed at the old man’s request, for how could such a wretched creature imagine that he could be admitted to the palace of the great king Lycaon and his fifty noble sons? But still, they told the king, and Lycaon and his sons came to the windows and balconies of the palace to gawp, and they laughed, too. But rather than send him away with a kick, as they would normally do, Lycaon decided to grant the extraordinary request. “My boys,” said the king as he howled with laughter, “we can amuse ourselves with this one.”

And so the stranger was ushered into the dining hall of the palace, and given an honoured place at the table.

“Old man,” said Lycaon with a grin, “tonight you shall be served a dish such as you have never been served before!”

And with that, he took his fifty sons into the kitchen, all of them laughing and laughing, though only Lycaon seemed to know what he was laughing about, for amidst the laughter, his sons exchanged a few uneasy glances. When they got to the kitchen out of sight of the old man, Lycaon pounced on long-locked Nyctimus, the youngest of his sons, and bashed his face on the stone floor. Then he drew his sword, and before Nyctimus could get up, he cut his throat with as little feeling as a shepherd kills a dog turned blind and useless with age. The bright blood poured onto the floor like young, well-mixed wine, and it pooled around the feet of the forty-nine princes, who watched as their father cut up and butchered their brother. And Lycaon was laughing as he went about his work, laughing crazily, and his forty-nine sons watched him laugh, and soon they were laughing too, and, in his last dying breaths, even Nyctimus laughed, for in his last moments of life as the last drops of blood drained from his shivering body, he understood the joke.

The stranger, seated at his honoured place at the table, had begun to wonder if he would ever get his food. His stomach rumbled angrily. What could be the cause of all this delay? Certainly, the dish Lycaon had in store for him must be wonderful indeed if it required so much time to prepare. Just as the stranger was on the point of sending a servant to ask how much longer he would have to wait, in came Lycaon, followed by his forty-nine sons. The stranger counted them. Had there not been fifty when they were here before?

“Old man,” said Lycaon, “I promised you a dish such as you have never been served before, and that is what you shall have.”

He clapped his hands, and a servant entered, bearing an enormous, dazzling golden bowl. The servant bowed slightly before the stranger and set the bowl in front of him. The stranger peered at its steaming contents and sniffed its aroma. A stew of some kind. He stirred it slowly with a silver spoon.

“I thank you,” he said, “great king of Arcadia, for the honour of this meal. What is it, if I may ask?”

“You may ask,” said the king graciously, “and I will answer. We Arcadians eat this before toil and before battle. No feast is without it. It will give you warmth, health and strength. The power of a God will course through your hands”.

As Lycaon spoke this last word, a slender hand, severed roughly at the wrist, surfaced in the stew while the stranger stirred and stirred. Lycaon could restrain himself no longer. He clutched his stomach and staggered on his feet as he broke into howling, uncontrollable laughter, tears rolling down his cheeks. And his forty-nine sons started laughing, and they could not control their laughter, and they howled and howled and rolled about on the floor. And a sudden gust of wind blew in through the window, and blew over the top of the enormous golden bowl, and it seemed as if a faint howl of laughter issued from the bowl as the wind passed over it. The great dining hall of the royal palace of Arcadia echoed in howling laughter.

The stranger, too, laughed—but not for long. His laughter froze. His eyes flashed. His stern brow became even sterner with fury.

“Howl on, you animals,” he said quietly. “Howl on, and never cease your howling.”

And Lycaon and his sons kept howling with laughter, howling and howling, until their howls became louder and longer, and seemed less like laughter, until they were not laughing at all, only howling. And they did not stop howling as they saw, with horror, their mouths and noses grow and grow into long, hairy, whiskered snouts. They did not stop howling as claws sprouted from their hands and feet, as their ears spurted outwards and upwards, as tails shot out at the base of their backs. Lycaon and his forty-nine sons did not stop howling as they felt themselves forced onto all fours, as their torn clothes dropped to the floor, as sharp teeth drove their way painfully through their aching gums. They did not stop howling as they beheld the wretched old stranger throw off his rags and reveal himself as mighty Zeus, the cloud-compeller, two blinding beams of light blazing from beneath his stern brow.

“Gaze on me, you wolves,” he bellowed, “and know that your punishment comes from the king of the gods!”

With that, he vanished, and overhead there was a deafening peal of thunder, and lightning struck the palace, and the wind and the rain battered and lashed the people of Arcadia, who became frightened, terrified, and called upon sky-ruling Zeus to forgive them, swearing that never again would they descend to the evils that had been their custom for so long, that they would change their ways, that they would show kindness and consideration and seek always to help those in need, and try very hard not to murder them. Slowly, the clouds dispersed; the rain eased; the wind died down; the thunder and lightning ceased. The people of Arcadia rubbed their eyes and beheld the ruins of the palace, and amidst the smoking ruins, a pack of wolves, fifty of them, blind and howling. The people of Arcadia chased the wolves deep into the forests, where they have since remained—howling, forever howling.

I have a post up at the Cambridge Secondary English P.G.C.E. blog. It’s about teaching choral reading using the excellent audio series War with Troy, in which storytellers Hugh Lupton and Daniel Morden superbly retell the story of the Trojan War. You can read my post HERE.

One of the advantages of being a student again is having access to a good library. I’ve long been intrigued by an obscure little book called The Eater of Darkness, a sci-fi pastiche and early example of Surrealist fiction in English, written by an American expatriate in Paris who later became a well-known art critic (to whom we owe the term ‘Abstract Expressionism’)—and what could be more intriguing than that? My curiosity about had been frustrated for years by the scarcity and expense of available copies: first editions are on sale for about £300 at the lower end of the scale, and more than £1,000 at the higher end, while even the 1959 reissue would set you back by about £30—all for a slender paperback of less than 200 pages.* When I learned that my university library has a copy of the first edition, I was delighted, but there was also a touch of trepidation that the high expectations I’d been building up would be confronted with a dry, justly-forgotten period piece, a curio of strictly academic interest. In fact, the book is a hoot from beginning to end.

The hero or anti-hero is Charles Dograr, a young man who becomes involved for no discernible reason in a murderous crime wave masterminded by ‘the old gentleman’, the many-aliased inventor of the ‘oculascope’, a machine which can kill at great distance and to a high degree of accuracy by means of what Dograr calls an ‘x-ray bullet’ (the diagram Coates includes of this apparatus is less Heath Robinson and more Joan Miró). When Dograr first looks through the oculascope, his vision is directed through a series of things, the series becoming one of those long, amusingly miscellaneous lists that seldom come as a surprise in modernist literature:**

a cigar humidor

the mechanism of an alarm clock

a roll of toilet paper

the chain of an electric light fixture

four pages of the New York Journal

the hand of the reader

an orange

an El station turnstile

a goldfish bowl.

a cushion

the calf of Fannie Brice’s leg

two kissing lips

an iron handrail

a corset string

a garbage can

a plate of ham sandwiches

Laurence Vail

Peggy Vail

a pack of cards

a stiletto

a glass eye

two felt slippers

a cigarette holder

an umbrella

an art-bronze bookrack

Harold Stearns

Floyd Dell

a clogged drain pipe

a sheaf of Shulte Cigar Store coupons

Malcolm Cowley

a tree

a bottle of gin

a street lamp in an open park. . .

You might expect to find some of these objects in fragmentary form in a Cubist painting, but while many of them can be visualized individually, the action that is supposed to link them is all but inconceivable—the curiosities and wonders of modern physics travestied into utter nonsense. The old gentleman’s expression of his scientific and philosophical creed, which defines ‘homo physico-philosophicus’ as a person to whom physics and metaphysics are synonymous, becomes ever more pseudo-scientific and nonsensical (‘And Form, therefor, is capable of indefinite projection through space—provided that the co-related energy be entirely endogenous !’).

It is entirely appropriate, then, that the figure at the centre of these shenanigans is an absurd bundle of mannerisms, attitudes and behaviours that can in no way be contained within a psychologically convincing character, even an insane one. Charles Dograr: the sensitive soul who murders without pity or motivation, who impersonates the relative of one of his victims, who fantasizes that innocent pedestrians are bent on robbing and killing him, who buys a bunch of silk shirts and music records before abruptly dumping them in the trash, who delivers a solemn hymn to plant-life (‘The vegetables are not vindictive’). At the centre of a nonsensical plot is a nonsensical protagonist, nothing but an occasion for authorial fun and games:

For Charles Dograr was one of those rare souls whose spirit seems to have been compounded, as it were, of more fragile substance, of emotion more volatile, perception more finely tunable than the rest, so that he rode currents of intuition that others sank through seeking the rock-bottom of logic, and was uplifted and exalted by the transcendental vapors of a perhaps earthly—even, to continue the figure ad locandum, miry—concept into which others, trudging, stuck bogged and bemisted.

So sound moved him more than hearing, vision more than sight, and his instinct sucked Truth, like honey, from the flower of Life, disdaining the syllogistic distillation of the comb. Briefly, he listened to the melody, not the words, of the Eternal Song, and he was just the person—perhaps the only one alive—to imagine there was any discoverable meaning in such a passage as this, when he found it in a book.

The punchline is anything but subtle, yet it made me laugh. Funnier still are the crazed antics that ensue from Dograr’s encounters with life in a 20th-century metropolis, a mode of existence which cannot accommodate a walking absurdity such as Dograr without chaos being the result. And yet from that chaos, there emerges a critique of the hidden absurdities of technological, capitalist modernity, in all its strait-laced humbug. Take, for instance, the moment when Dograr bumps into a total stranger on a busy street—an everyday occurrence in a major city, but one transformed into an extraordinary moment when Dograr, instead of exchanging the customary apologetic looks and walking on, beats the man senseless. A crowd of passers-by gathers around him to provide an audience for a rousing speech that extricates him from any unpleasantness (the idiosyncrasies of punctuation have been retained):

“This man would drag down the Fair Name of American Womanhood into the Mire of Infamy,” he proclaimed, pointing to his recumbent antagonist. “Bearing the outward semblance of Honor, Uprightness, and the Spirit of Fair-Play that is typical of American Manhood, he worms his way into the sanctity of the American Home ,and there works his foul way unobserved. That man—”, he drew himself to his full height—“was trying to get my wife to run away with him. And besides, he’s a Bolshevist !”

A confused murmur rose from the hoarse throats of the crowd—a mingling of cheers for Charles, and threats for the unconscious victim. Charles, with charming modesty, raised a deprecative hand, and vanished in the direction of the Grand Central.

Naturally, Dograr is unmarried. His puffed-up rhetoric, parodying that of the red-baiting press and of the blustering politicians who operate symbiotically with it, is all too effective; the unfortunate pedestrian becomes one of the novel’s several hapless victims—ordinary, unremarkable citizens who become entangled at random in the mechanisms of events beyond their comprehension. This fellow gets off relatively lightly; others are blown up or have their brains fried. The political reading that is available here is concurrent with the sense of a writer enjoying himself, messing around with meaningless non-lives and goofily disposing of them. The skewering of rhetorical clichés is expertly done, but fairly elementary; what gives the joke its kick is the little absurd touch at the end—the ‘deprecative hand’ raised ‘with charming modesty’—and it is this that caused me to disturb the peace of the library’s Rare Books reading room with one of several very audible giggles.

This is a funny book, as funny as Flann O’Brien in full flight. The highpoint of its humour is, I think, when the author promises to describe the habitation and person of a young lady, only to withhold most of the detail on the grounds of decency:

In fact, had the reader been led actually to open the door of that chamber at the hour mentioned, the first glance about the walls of the room would have led him (if he be as mature in experience as we suppose he is) to close the door softly and make his way out to the street again (if he be as decent and upright a man as we pray him to be).

Once again, Coates is not content with the joke as it stands, hilarious though it is, but takes it to even greater heights of comic invention:

In other words, the lady was a prostitute. In the flesh, the reader must have fled from her—or paid ten dollars to investigate her charms. We see no valid reason why the readers of this book should be otherwise dealt with. On receipt of ten dollars we will forward in plain wrapper a complete and catalogued (illustrated) description of Madame Helène Montmorency.

At this point, I dissolved into something far less controlled and dignified than mere giggles.

The book is full of such delightful tricks: a column of a newspaper report running alongside the novelistic narrative, the report degenerating into gibberish; a purple-prosed Scotland Yard report (‘the heavy-shouldered, the ruffian sea, the ruffed and petticoated, creaming sea, its void immensity’); sly cracks at the conventions of pulp sensationalism (‘beautiful and unashamed in the curving redundancy of her body’s loveliness beneath the unconcealing silk chemise’); mimicry of cinematic technique (captions accompanying short, ‘montaged’ scenes, references to irises closing); unhelpful mock-scholarly footnotes, including one which abuses the author for his ignorance of the elementary principles of plot construction. These tricks alone would be enough to make the book a comic masterpiece, but Coates can do more besides, for there also marvellous passages that strike other notes, notes that convey something of the wonderment and anguish of being alive, of being surrounded by questions that have no answer. I will say nothing of the narrative frame into which Coates inserts his ludicrous thriller plot, except to note that it leads to an ending that is at once audacious, unsurprising, appropriately anti-climactic and oddly beautiful. It is a sad quirk of literary history that this book has so little reputation; it will be a minor tragedy if this situation continues.

*There is a cheaper reprint from 2012 by Olympia Press, but to judge from the Amazon reviews, this seems to be best avoided.

**The people named in this list are all historical figures. Fannie (or Fanny) Brice was a stage and radio star; Laurence Vail was a writer and artist; his wife Peggy (better known as Peggy Guggenheim) was an art collector; Harold Stearns, Floyd Dell and Malcolm Cowley were all writers.